- Safety & Recalls

- Regulatory Updates

- Drug Coverage

- COPD

- Cardiovascular

- Obstetrics-Gynecology & Women's Health

- Ophthalmology

- Clinical Pharmacology

- Pediatrics

- Urology

- Pharmacy

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Allergy, Immunology, and ENT

- Musculoskeletal/Rheumatology

- Respiratory

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Dermatology

- Oncology

Equivalent dosing of irbesartan, valsartan, and losartan identified through formulary switch at a Veterans Affairs medical center

Until 2005, irbesartan was the only ARB available on the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system's national formulary. In 2005, irbesartan was removed from the formulary and was replaced with valsartan and losartan. For those patients who were to continue ARB therapy via a switch to either losartan or valsartan, dosing guidelines were created by the Veterans Integrated System Network 7 to facilitate the change. These guidelines suggested that patients taking irbesartan 150 mg once daily be treated with either valsartan 80 mg or losartan 50 mg once daily and that patients taking irbesartan 300 mg once daily be treated with either valsartan 160 mg or losartan 100 mg once daily. To determine if the dosing guidelines resulted in equal antihypertensive effectiveness, we carried out a retrospective chart review, examining the cases of 86 patients at the William Jennings Bryan Dorn VA Medical Center in Columbia, South Carolina, who had switched from irbesartan to either losartan or valsartan.

Key Points

Abstract

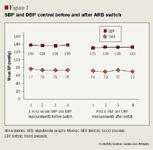

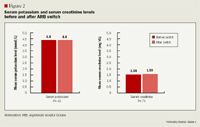

Until 2005, irbesartan was the only ARB available on the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system's national formulary. In 2005, irbesartan was removed from the formulary and was replaced with valsartan and losartan. For those patients who were to continue ARB therapy via a switch to either losartan or valsartan, dosing guidelines were created by the Veterans Integrated System Network 7 to facilitate the change. These guidelines suggested that patients taking irbesartan 150 mg once daily be treated with either valsartan 80 mg or losartan 50 mg once daily and that patients taking irbesartan 300 mg once daily be treated with either valsartan 160 mg or losartan 100 mg once daily. To determine if the dosing guidelines resulted in equal antihypertensive effectiveness, we carried out a retrospective chart review, examining the cases of 86 patients at the William Jennings Bryan Dorn VA Medical Center in Columbia, South Carolina, who had switched from irbesartan to either losartan or valsartan; 11 of these patients had been taking irbesartan 75 mg once daily and were switched to valsartan 40 mg or losartan 25 mg once daily based on an extrapolation of the guidelines. The 4 most recent consecutive blood pressure (BP) measurements before the switch were compared with the first 4 consecutive BP measurements after the switch. Additionally, the 3 most recent serum creatinine and serum potassium values before the switch were compared with the first 3 values after the switch. No statistically significant difference was observed between the BP measurements taken before and after the switch (F [3,209]=.11; P=.95). No significant changes were observed in serum potassium (P=.42) or serum creatinine (P=.71) values. Although the generalizability of these results may be limited, as the study was restricted to a small, mostly male population of veterans, we believe that the results demonstrate the therapeutic equivalence of specific doses of irbesartan, losartan, and valsartan. (Formulary. 2008;43:14–20.)

ACE inhibitors have been studied in a variety of patient populations, including in patients with HF, CKD, diabetes, chronic stable angina, MI, and stroke.5–10 ACE inhibitors produce their pharmacologic effects by blocking the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, which is a potent vasoconstrictor and stimulator of aldosterone secretion.11 Additionally, ACE inhibitors block the degradation of bradykinin, which is a vasodilator; bradykinin is also one of the molecules responsible for the side effect of dry cough, which occurs in ≤20% of patients treated with an ACE inhibitor.11

Like ACE inhibitors, ARBs also inhibit angiotensin II, but they exert their effect through direct inhibition of angiotensin II type 1 receptors.11 As a result, ARBs induce vasodilation and aldosterone inhibition but do not affect the breakdown of bradykinin and, therefore, are unlikely to be associated with cough.11 Like ACE inhibitors, ARBs have also been studied in several patient groups with hypertension and specific compelling indications including HF, MI, and diabetic nephropathy.12–17

Potential adverse effects that may occur with both ACE inhibitors and ARBs include hyperkalemia, kidney insufficiency, angioedema, and orthostatic hypotension.11 When patients begin treatment with either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB, their BP, serum potassium, blood urea nitrogen, and serum creatinine levels should be monitored.11 Angioedema generally occurs less often with ARBs than with ACE inhibitors, but cross-reactivity is possible.11 Therefore, ARBs should be used with caution in patients with a history of angioedema.11 Overall, ARBs seem to be the most well-tolerated agents among the antihypertensive drugs that are available.18

In addition to JNC 7, other national guidelines also describe appropriate therapeutic uses for ACE inhibitors and ARBs.5–7 The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines recommend ACE inhibitors or ARBs (in those patients intolerant to ACE inhibitors) for all post-MI patients with signs of HF and for those with a low ejection fraction.5 ACE inhibitors are recommended by the AHA/ACC for all patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction HF, and ARBs are considered to be a "reasonable alternative" in patients who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors.5 The National Kidney Foundation (NKF) recommends that patients with diabetic or nondiabetic CKD and with or without hypertension be treated with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.6 The NKF makes no claims of superiority between the classes, as no current trial compares the 2 classes of drugs head-to-head in patients with kidney disease.6 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) makes a similar recommendation in stating that ACE inhibitors and ARBs should be used in diabetic patients to treat any degree of albuminuria, a possible precursor to CKD.7

ARBs and the Veterans Affairs healthcare system. As of fiscal year 2006, 7.9 million veterans were enrolled in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system, which provides comprehensive healthcare and prescription drug coverage.19 In order for all eligible beneficiaries to receive the medication therapies that they need, the VA healthcare system has a medication formulary system in place (the VA national formulary [VANF]) that ensures appropriate and efficient use of medications. Currently, the VANF lists ARBs as second-line agents after ACE inhibitors for the treatment of VA beneficiaries with hypertension, HF, and proteinuria.20 ARBs are reserved for those patients who have an adverse reaction to ACE inhibitor therapy. In the case of proteinuria, ARBs may be added to ACE inhibitor therapy if proteinuria persists despite maximal ACE inhibitor therapy.20

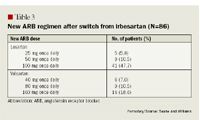

Until 2005, irbesartan was the only ARB available on the VANF. In 2005, irbesartan was removed from the VANF and replaced with valsartan and losartan because of contract changes that made valsartan and losartan the most cost-efficient ARBs available for use by the VA healthcare system. For patients taking irbesartan at that time, a switch in therapy was mandated. Potential options for this therapeutic change included valsartan, losartan, ACE inhibitor therapy (if the patient had no prior history of ACE inhibitor use), or an antihypertensive agent from a class other than ACE inhibitors or ARBs (if the patient had no compelling indication for ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy). For those patients who were to continue with ARB therapy via a switch to either losartan or valsartan, dosing guidelines were created by the Veterans Integrated System Network 7 (VISN 7) to facilitate the change. These guidelines suggested that patients taking irbesartan 150 mg once daily be switched to valsartan 80 mg or losartan 50 mg once daily and that patients taking irbesartan 300 mg once daily be switched to valsartan 160 mg or losartan 100 mg once daily. Patients with HF were switched to valsartan, and patients with diabetes were switched to losartan. If no comorbidity was present, the choice of agent was left to the prescriber's discretion.

Although therapeutic interchanges among ARBs may occur in healthcare systems throughout the United States because of formulary restrictions or drug availability, little information has been published describing the protocols that guide these switches or the effects of such switches on BP measurements, serum creatinine levels, or serum potassium levels. Therefore, at the William Jennings Bryan Dorn VA Medical Center (Dorn) located in Columbia, South Carolina, we undertook a study to retrospectively review the cases of patients who were switched from irbesartan to losartan or valsartan because of the formulary changes described earlier. This study reviewed the cases of patients from Dorn and its outlying community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) who made this ARB switch to determine if the new ARB dosing provided BP control equivalent to that of the previously used irbesartan regimen. Secondarily, serum creatinine and serum potassium levels were evaluated to determine if the dosing switch resulted in similar adverse-effect profiles. The hypothesis of this study was that valsartan 80 mg or losartan 50 mg once daily provided BP control similar to that provided by irbesartan 150 mg once daily and that valsartan 160 mg and losartan 100 mg once daily provided BP control similar to that provided by irbesartan 300 mg once daily. Additionally, it was expected that these switches did not cause significant changes in serum potassium or serum creatinine levels.

METHODS

A list of patients treated with irbesartan from June 2005 to July 2005 was extracted from the drug dispensing records at Dorn, and each patient was evaluated for inclusion in this retrospective review. To be included, patients must have been switched from irbesartan 150 mg once daily to valsartan 80 mg or losartan 50 mg once daily or from irbesartan 300 mg once daily to valsartan 160 mg or losartan 100 mg once daily according to the VISN 7 guidelines. Based on an extrapolation of these guidelines, patients were also included if they were taking irbesartan 75 mg once daily and were switched to either valsartan 40 mg or losartan 25 mg once daily. Patients must have been receiving each drug (irbesartan before the switch and valsartan or losartan after the switch) for ≥2 weeks for the treatment of hypertension and/or for another compelling indication for ARB therapy such as diabetes, CKD, or HF. Patients who switched from irbesartan to an ACE inhibitor (eg, lisinopril, fosinopril, or ramipril) or to any drug other than valsartan or losartan were excluded from the study. Those taking irbesartan/ hydrochlorothiazide were also excluded from the study, as a change in hydro-chlorothiazide dosing has the potential to affect serum potassium levels.

Once the study population was identified, the 4 most recent BP values recorded before the switch were compared with the first 4 BP values recorded after the switch. The 3 most recent serum potassium and serum creatinine levels recorded before the switch were compared with the first 3 values recorded after the switch. Patients with only 1 observation either before or after the switch were excluded. The mean score of available observations was substituted for missing observations in the period before the switch for patients who had only 2 or 3 available BP measurements before the switch and for patients with only 2 serum creatinine or serum potassium measurements before the switch. When BP, serum creatinine, or serum potassium measurements were missing after the switch, the last observation was carried forward to complete the data set.

For this study, we used a doubly multivariate, repeated-measure, mixed-model ANOVA to compare SBPs and DBPs before and after the switch, and a repeated-measure, mixed-model ANOVA to compare serum creatinine and serum potassium values before and after the switch. The F test was used to compare variances in SBP and DBP. The value of F is a ratio of 1 variance to another; therefore, values very different from 1 are indicative of statistical significance.

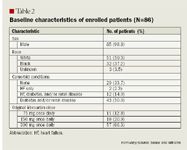

Demographic data such as age, race, sex, and comorbidities were also recorded. The presence of comorbid conditions was determined based on whether particular conditions were documented within patients' medical records.

It was expected that this ARB switch had the potential to affect >600 patients at Dorn and its affiliated CBOCs. It was also expected that the medication switch would not cause a significant difference in BP control, serum potassium levels, or serum creatinine levels.

RESULTS

CONCLUSION

DISCUSSION

Our findings were limited by the fact that this was a retrospective chart review. The generalizability of these results also may be limited, as the study was restricted to a small, mostly male population of veterans. We did not have the ability to standardize the dosing of any additional antihypertensive agents, which may or may not have caused additional changes in BP measurements or in serum creatinine or serum potassium levels. Despite these concerns, we believe that using a doubly multivariate, repeated-measure, mixed-model ANOVA for BP and a repeated-measure, mixed-model ANOVA for serum creatinine and serum potassium levels provided sufficient power to determine whether even a small difference between treatment groups existed. This study is promising in that it demonstrates the therapeutic equivalence of specific doses of 3 drugs within the ARB class. This makes it possible for practitioners to choose an ARB based on clinical trial data and cost-effectiveness.

Dr Sease is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Outcome Sciences, South Carolina College of Pharmacy, University of South Carolina, Columbia. Dr Williams was a primary care pharmacy practice resident at the William Jennings Bryan Dorn Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Columbia, South Carolina, from 2006 to 2007. He is now a pharmacist at Naval Hospital Beaufort, Beaufort, South Carolina.

Acknowledgment: The authors wish to thank Jack P. Ginsberg, PhD, at the Williams Jennings Bryan Dorn Veterans Affairs Medical Center, for his assistance with this article.

Disclosure Information: As related to products discussed in this article: Dr Sease discloses that she has served on the speakers' bureau for Novartis. Dr Williams reports no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

1. High blood pressure statistics. American Heart Association website. http:// http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=2139. Updated July 27, 2007. Accessed December 18, 2007.

2. Ong KL, Cheung BM, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KS. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75.

3. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R; Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies [erratum in Lancet. 2003;361:1060]. Lancet. 2002;360: 1903–1913.

4. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252.

5. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American College of Chest Physicians; International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; Heart Rhythm Society. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): Developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112: e154–e235.

6. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43 (5 suppl 1):S1–S290.

7. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2007. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30:S4–S41.

8. Fox KM; European Trial on Reduction of Cardiac Events with Perindopril in Stable Coronary Artery Disease Investigators. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study). Lancet. 2003; 362:782–788.

9. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators [errata in N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1376 and N Engl J Med. 2000;342:748]. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145–153.

10. PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack [errata in Lancet. 2001;358:1556 and Lancet. 2002;359: 2120]. Lancet. 2001;358:1033–1041.

11. Saseen JJ, Carter BL. Hypertension. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies Inc; 2005:185–217.

12. Cohn JN, Tognoni G; Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1667–1675.

13. Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, et al; CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: The CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet. 2003;362:759–766.

14. Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al; Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial Investigators. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both [erratum in N Engl J Med. 2004;350:203]. N Engl J Med. 2003;349: 1893–1906.

15. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al; RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–869.

16. Parving HH, Lehnert H, Brochner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Andersen S, Arner P; Irbesartan in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria Study Group. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345: 870–878.

17. Viberti G, Wheeldon NM; Microalbuminuria Reduction with Valsartan (MARVAL) Study Investigators. Microalbuminuria reduction with valsartan in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A blood pressure-independent effect. Circulation. 2002;106: 672–678.

18. Conlin PR, Gerth WC, Fox J, Roehm JB, Boccuzzi SJ. Four-year persistence patterns among patients initiating therapy with the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan versus other antihypertensive drug classes. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1999–2010.

19. VA benefits and health care utilization. United States Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www1.va.gov/vetdata/docs/4X6_fall07_sharepoint.pdf. Updated October 25, 2007. Accessed December 18, 2007.

20. VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management–Strategic Healthcare Group and Medical Advisory Panel. Angiotensin II receptor antagonist criteria for use in veteran patients. United States Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.pbm.va.gov/criteria/AIIRA.pdf. Published August 2001. Updated March 2005. Accessed December 18, 2007.

FDA Approves Combination Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

March 25th 2024J&J’s Opsynvi is single-tablet combination of macitentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, and tadalafil, a PDE5 inhibitor. It will be priced on parity with Opsumit, which is also a J&J product to treat patients with PAH.

FDA Issues Complete Response Letter for Onpattro in Heart Failure Indication

October 9th 2023Alnylam Pharmaceuticals will no longer pursue this indication of Onpattro and will instead on focus on a label expansion for Amvuttra, which is in phase 3 development to treat patients with cardiomyopathy of ATTR amyloidosis.