- Safety & Recalls

- Regulatory Updates

- Drug Coverage

- COPD

- Cardiovascular

- Obstetrics-Gynecology & Women's Health

- Ophthalmology

- Clinical Pharmacology

- Pediatrics

- Urology

- Pharmacy

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Allergy, Immunology, and ENT

- Musculoskeletal/Rheumatology

- Respiratory

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Dermatology

- Oncology

Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation: underlying causes and available treatments

This review examines the underlying causes associated with ED and PE and evaluates currently available treatment options and those under investigation.

Key Points

Abstract

Erectile and ejaculatory disorders comprise the most prevalent sexual disorders in men, with erectile dysfunction (ED) primarily affecting aging men who have coexisting morbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Premature ejaculation (PE) can affect men of all ages and is not typically associated with underlying organic disorders but is believed to be associated with imbalances in serotonin neurotransmission. The availability of oral phosphodiesterase inhibitors has revolutionized the management of ED, replacing less-desirable older products associated with more side effects. Although many efficacious treatment options are currently available and recommended for the management of PE, several challenges remain in bringing the first desirable, safe, and effective FDA-approved drug to the US market. This review examines the underlying causes associated with ED and PE and evaluates currently available treatment options and those under investigation. (Formulary. 2010;45:17-27.)

Erectile dysfunction (ED) and ejaculatory disorders such as premature ejaculation (PE) are considered the most common types of sexual dysfunction in men. "The inability to achieve or maintain an erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance," is a commonly accepted definition of impotence by the National Institutes of Health; however it is now recognized by the American Urological Association (AUA) as ED.1 ED reportedly affects up to 40% of men between the ages of 40 and 70 and is more likely to develop with aging.2-4 Despite broad consensus on a single definition, PE is commonly characterized by the inability to delay ejaculation, which occurs before or soon after the initiation of intercourse and is subsequently associated with feelings of distress or frustration.5,6 Unlike ED which is more prevalent in older men, PE is considered one of the most common male sexual disorders and occurs with similar frequency in men, independent of age.5,7

PENILE ANATOMY AND NORMAL ERECTION PHYSIOLOGY

The penis is comprised of several key structures: the corpus cavernosum encased within the tunica albuginea, the corpus spongiosum containing the urethra, and the extensive vascular system of arteries and veins.8 In the flaccid state, penile smooth muscle tissue is contracted and arterial blood flow which supplies the sinusoidal cavities within the pair of corpora cavernosa is equal to venous drainage from them. With the exception of nocturnal penile tumescence, a sensory stimulus initiates the erectile process via two coordinated pathways involving vasoactive substances, prostaglandins, and circulating catecholamines.9,10 Nitric oxide, which is synthesized and released from endothelial cells, crosses into smooth muscle cells and enhances the activity of guanylate cyclase, which catalyzes the formation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) from guanosine triphosphate (GTP). The second pathway involves prostaglandin E1-mediated activation of G proteins within smooth muscle cells, followed by stimulation of adenylate cyclase and increased production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) from adenosine triphosphate (ATP).9 By decreasing intracellular calcium concentrations, both cGMP and cAMP cause smooth muscle relaxation, which leads to increased cavernosal arterial blood flow and decreased venous drainage resulting in an erection.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ED

Neurogenic disorders involving the central nervous system (CNS) or peripheral nervous system such as stroke, spinal cord injury, Parkinson's disease, and multiple sclerosis have also been associated with ED. Furthermore, patients with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), Peyronie's disease, hypogonadism, or those who have had a radical prostatectomy secondary to prostate cancer are at greater risk of developing ED.12

Drug induced causes of erectile dysfunction are common and can complicate the medical management of underlying conditions associated with ED such as hypertension, depression, and BPH (Table 1). Beta blockers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and the uroselective alpha adrenergic receptor antagonists have been associated with the loss of libido or ejaculatory disorders, which can result in drug discontinuation by patients and suboptimal treatment of these conditions. Researchers examining the role of drug exposures in the prevalence of erectile dysfunction found that hypertensive patients taking selected antihypertensive therapy increased the odds of ED prevalence, compared with patients not taking selected antihypertensive therapy (odds ratio [OR] 3.0, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.6-5.9).13

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OUTCOME MEASURES

Despite the high prevalence of erectile disorders, identifying the presence of this condition remains challenging for the physician as patients are often reluctant to discuss this sensitive problem. Although patients may be more inclined to share these issues when the discussion is initiated by their healthcare provider, physicians' themselves may also have some uneasiness with this conversation. A recent review of several studies found that the prompt recognition and treatment of ED symptoms associated with underlying endothelial cell dysfunction may improve ED related outcomes by decreasing the development or progression of vascular comorbidities.11

Approximately 80% of men diagnosed with ED will have organic disease; thus the AUA diagnosis and treatment guidelines recommend a thorough medical history and physical examination for all patients with suspected ED to identify underlying vascular, neurologic, or hormonal abnormalities.14 The medical history should include a complete assessment of risk factors associated with organic ED and identification of comorbidities (ie, Peyronie's disease, history of penile surgery) that may present unique challenges to developing an effective treatment response. Patients should also be assessed for co-occurring anxiety or depressive disorders to rule out a psychogenic etiology.

Several tools have been developed to assess treatment outcomes such as the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), the Erectile Dysfunction of Inventory of Treatment Satisfaction (EDITS), and the Premature Ejaculation Tool. The IIEF is a self-administered questionnaire that contains 15 questions which assess several domains, such as: erectile function, orgasm, sexual desire, and satisfaction.1 The IIEF-5 is an abbreviated version of the IIEF which serves as a useful measure of treatment response and is generally more applicable to a clinical practice setting. Patient diaries, such as the Sexual Encounter Profile (SEP), are also commonly utilized to document improvement in clinical outcomes. Questions 2 and 3 from the SEP address a patient's ability to attain an erection sufficient for intercourse (SEP2) and the maintenance of the erection through completion of intercourse (SEP3).

PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

Currently available agents for the management of ED include: the oral phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE 5) inhibitors, intraurethral and intracavernous prostaglandin E1 formulations, injectable phentolamine and papaverine, and testosterone preparations. Trazodone, yohimbine, and herbal products have been utilized in the treatment of ED but are not recommended for use by the AUA.1

PDE 5 INHIBITORS

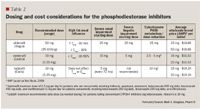

The arrival of sildenafil (Viagra) to the US market in 1998 was the first FDA approved oral PDE 5 inhibitor. It was followed shortly by vardenafil (Levitra) and tadalafil (Cialis) in 2003, marking a shift in the management of ED as more patients began to seek treatment with the availability of these more convenient pharmacologic options. All 3 agents exert their effect by selectively blocking PDE 5 in cavernosal smooth muscle cells, which leads to a greater concentration of cGMP, thereby enhancing the effects of smooth muscle relaxation and cavernosal blood flow resulting in prolonged erectile function.

Clinical efficacy. The efficacy of the PDE 5 inhibitors has been demonstrated in several patient populations with ED due to organic and psychogenic causes. In a pooled analysis of several sildenafil studies, 63%, 74%, and 82% of sildenafil-treated patients who received 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg, respectively, reported improvement in their erections, compared to only 24% of placebo-treated patients.15 Similar results were observed in vardenafil-treated patients in whom escalating doses were also associated with better outcomes, between 58% and 66% of patients on vardenafil reported success with intercourse regardless of the drug dose.18 Two studies in tadalafil-treated patients showed that 62% and 77% of patients were successful with SEP2, compared to 39% and 43% of placebo-treated patients, respectively (P<.001). For SEP3, 50% and 64% of patients indicated successful completion of intercourse, compared to 25% and 23% of patients, respectively (P<.001).17 Despite a lack of trials that compare these agents, all are considered equally effective for the treatment of ED by the AUA.1,19

As a result of their mild vasodilatory effects, caution should be exercised when the PDE 5 inhibitors are coadministered with other antihypertensive agents. The administration of nitrate-containing preparations are contraindicated with sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil due to the profound hypotensive effects of this drug combination. Furthermore, because of the underlying association of ED with cardiovascular disease, clinicians should carefully assess whether these agents are indicated in a particular patient. The Princeton Consensus Conference was developed to stratify ED patients by cardiovascular status into low-, intermediate, and high-risk categories to assist practitioners in determining whether a particular patient can safely engage in sexual intercourse.20 The Second Princeton Consensus Conference reaffirmed these criteria in 2004.21

Transient visual changes and disturbances in color vision have been reported rarely with the administration of the PDE 5 inhibitors, because these agents are known to exhibit partial selectivity for the PDE 6 enzyme that is present in rod and cone photoreceptors.22 More recent postmarketing reports of decreased vision or complete loss of vision as a result of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) have led to further investigation of a temporal relationship between the PDE 5 inhibitors and this condition. NAION is an uncommon visual disorder that can lead to decreased visual acuity as a result of a swollen or "crowded optic disc" and is typically more prevalent in patients with a small cup-to-disc ratio and comorbidities such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, and coagulation disorders.22 Given that the risk factors for NAION share a close association with underlying disorders observed in ED patients receiving treatment with PDE 5 inhibitors, it remains unclear whether these agents increase the likelihood of developing NAION.

PROSTAGLANDIN E1 AND VASOACTIVE FORMULATIONS

Prior to the market arrival of the oral PDE 5 inhibitors, alprostadil, a prostaglandin E1 analog that facilitates the erectile response through cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation, was considered the treatment of choice for the management of ED.12 Alprostadil remains the preferred second-line treatment option for patients who are unable to tolerate, or have an inadequate treatment response to the PDE 5 inhibitors.14 Alprostadil is commercially available as Caverject Impulse and Edex intracavernous injections, as well as Muse urethral suppositories. At the time of this review, Caverject Impulse is temporarily unavailable through the drug manufacturer.

Pharmacokinetics. Alprostadil, when administered via intracavernous injection, has a quick onset of action and typically results in an erection within 5 to 20 minutes.23 Patients who are ideal candidates for intracavernous therapy should receive thorough education and training on proper self-injection technique. Initial dosing and titration is performed within the physician's office utilizing the lowest dose necessary to produce a 30 to 60 minute erection sufficient for intercourse.24 The initial recommended dose of intracavernous alprostadil is 2.5 µg and should be titrated in 5 to 10 µg increments until a response is observed. The average doses used in clinical studies ranged from 10 to 20 µg and the recommended injection frequency is no more than 3 times weekly.23,24

Alprostadil urethral suppositories are absorbed through the urethral lining within 10 minutes and have a duration of action of about 30 to 60 minutes.25 Self administration of suppositories within the urethra can be challenging; patients should be closely supervised in the office setting during the initial treatment period. A low starting dose of 125 to 250 µg is recommended and may be titrated to 500 µg or 1,000 µg as tolerated.26,27

Clinical efficacy. Clinical studies evaluating the efficacy of alprostadil have generally found that the intracavernous injections are more effective than the urethral suppository formulations. In a randomized, open-label, multicenter study involving 111 patients, 82.2% of intracavernous administrations resulted in successful intercourse, compared to 47.4% of urethral alprostadil suppository administrations (P<.0001).28 Similar results were found in a study that compared intracavernous injection to urethral suppository use in 66 patients with ED. Of alprostadil injections, 85% led to intercourse, compared to only 55% of suppository administrations (P<.05).27

Precautions and adverse events. Both dosage formulations of alprostadil are administered locally and rapidly metabolized, making systemic side effects relatively uncommon with these agents. Local side effects such as penile pain associated with injection and urethral burning are the most common treatment-associated complications, occurring with variable incidence but reported in 17% to 37% of patients in clinical studies.23-25 Potentially serious side effects, such as prolonged erection and priapism are much less common and have been reported in approximately 1% of patients using alprostadil formulations.

Intracavernous papaverine and phentolamine, like alprostadil, are smooth muscle relaxants that facilitate the erectile process through the dilation of cavernosal arteries. Phentolamine lacks substantial effectiveness when used alone and papaverine monotherapy is associated with a higher incidence of prolonged erection and fibrosis so both drugs are typically combined and compounded at specialized pharmacies.12 The resulting product is referred to as "bimix." Another formulation called "trimix" is prepared with the addition of alprostadil. In clinical studies evaluating the combined use of all 3 vasoactive agents, the success rate has been comparable to alprostadil monotherapy. Therefore, the guidelines from AUA recommend that an initial trial of alprostadil monotherapy be considered in patients who are candidates for vasoactive therapy.12 For patients who fail alprostadil monotherapy, bimix and trimix formulations can be considered.

TESTOSTERONE PREPARATIONS

ED has been associated with low serum testosterone levels secondary to hormonal conditions such as hypogonadism, and testosterone replacement therapy has been shown to improve these symptoms in patients with androgen deficiency.29 Several testosterone replacement products are commercially available including: immediate and delayed release injections, a transdermal patch, topical skin gels, a buccal mucosa delivery system, and sterile pellet implants. The less-practical, short-acting testosterone propionate injection is administered several times a week and has been largely replaced by the lipid soluble ester formulations, testosterone cypionate and enanthate, which can be administered every 2 to 4 weeks. Two transdermal formulation patches (Testoderm and Testoderm TTS) designed for application to the scrotum are both currently unavailable through the drug manufacturer. One available non-scrotal transdermal delivery system (Androderm) is available in 2.5 mg and 5 mg systems, which should be reapplied nightly, every 24 hours. A 1% testosterone gel preparation (AndroGel) for trandermal delivery is available in 2.5 g and 5 g unit dose packets. A metered dose pump (Testim) is another 1% testosterone gel and is available in 5 g tubes. Patients should be instructed to wash hands after applying and avoid showering within 2 hours of application. A controlled-release mucoadhesive buccal delivery system (Striant) is designed to administer 30 mg of testosterone over a 12-hour period when applied above the incisor tooth twice daily. Implantable sterile cylindrical pellets (Testopel) are subcutaneously implanted by a healthcare professional and continuously deliver testosterone for 3 to 4 months or up to 6 months. Dosage should be individualized based on the minimum daily requirements of testosterone; two 75 mg pellets should be implanted for each 25 mg testosterone propionate required weekly.

Clinical efficacy and safety. Testosterone replacement therapy for the treatment of ED is controversial due to the lack of substantial data supporting the benefit of this treatment modality and the potential risk of long term side effects. A meta analysis found a significant mean erectile response rate in men with hypogonadism on testosterone therapy compared to placebo (65.4% vs 16.7%, P<.0001).30 However, a recent review found an inconsistent and non-significant effect on erectile function in patients with low testosterone (effect size, 0.80; 95% CI, -0.10-1.60).31 Testosterone treatment is generally well tolerated, with dermatologic reactions during transdermal replacement therapy being the most common side effects. The risks of developing prostate cancer while on long-term testosterone therapy have not been fully established, so close PSA monitoring is necessary.32

NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY TREATMENT OPTIONS

Vacuum Erection Devices (VEDs) are appealing nonpharmacologic options for patients because their efficacy is comparable to the PDE 5 inhibitors and they are associated with a relatively high margin of safety when used correctly. Several different VED products are available but all systems utilize a negative pressure vacuum chamber and elastic constriction ring at the base of the penis to facilitate and maintain an erection. Patient and partner success rates with VED therapy have been reported at 76% and 74%, respectively.12 The most common side effect associated with VED therapy is minor penile pain. Patients should only use VED products which contain a vacuum-limiting device to avoid injury to the penis due to excessive negative pressure.

The surgically implanted penile device was the first treatment available for ED patients almost 40 years ago, and today the penile prosthesis remains a viable treatment option for patients with a poor response to medical therapy. Currently available prosthetic devices are either noninflatable or inflatable. The non-inflatable or malleable products consist of a flexible rod that remains in a semi-rigid state and, although more reliable than the inflatable systems, they are not as desirable for many patients. The more desirable 3-piece inflatable products typically consist of a prosthetic cylinder implanted within each corpora which is connected to a fluid-filled reservoir and a pump in the base of the scrotum.

The most common complications associated with the penile prosthesis are device malfunction and infection. Technological advances have decreased the rate of malfunction and a recent review found a 10-year device survival rate of 79.4% in 2,384 patients with inflatable products.33 Similar advances have led to the development of antibiotic-coated devices, which have resulted in decreased infection rates.

TREATMENT OPTIONS CURRENTLY UNDER INVESTIGATION

Remarkable advances in the treatment of ED have been made over the past several years. In addition to the new PDE 5 inhibitors, several investigational agents with novel treatment targets and exciting strategies utilizing biotechnology, which may reverse the underlying disease pathology of ED, are in various phases of development.34

Several PDE 5 inhibitors are currently being evaluated in clinical studies. Avanafil is an ultra short-acting agent that is rapidly absorbed (Tmax 35 min) and eliminated (T1/2 < 1.5 hrs) and therefore may be an effective treatment option in patients who require nitrate therapy. Udenafil, mirodenafil, and slx-2101 have also shown improvement in erectile function, and udenafil's potential to modify the underlying ED pathology is being investigated.35

Novel treatment modalities currently being evaluated for ED include: topical alprostadil, dopamine agonists, melanocortins, Rho-kinase inhibitors, guanylate cyclase activators, as well as in vivo and ex vivo gene therapy. Alprostadil, which is formulated with SEPA gel or NexAct (both are topical absorption enhancing substances) is in phase 3 clinical studies and has shown improvements in erectile function, but it is unclear when or if this agent will be commercially available. Bremelanotide is a melanocortin receptor agonist with known effects on erectile function originating within the CNS and has shown significant improvements in erectile response after intranasal administration.36 The active form of Rho-kinase appears to augment the regulation of cavernosal smooth muscle contraction and detumesence, therefore, compounds that inhibit Rho-kinase are currently under development.34 The potential application of genetic technology, although still in early development, holds the most promise for the future of ED management. In animal studies testing intracavernous injections of a 'naked' DNA plasmid genetically encoded with a potassium channel activator, hSlo, the treatment has slowed the natural decline and maintained erectile function in rats for several months.36,37 A phase 1 study demonstrated a complete return of erectile function in 2 of 11 men with ED who received hSlo intracavernous therapy, which was well tolerated, as reported in a 2-year follow-up study. 38,39

PREMATURE EJACULATION

Pathophysiology. ED encompasses several disorders related to problems with ejaculation, such as premature ejaculation, delayed ejaculation, and anorgasmia.5 Of these, premature ejaculation is the most common and the focus of this discussion.

Premature ejaculation can be subdivided into a primary or secondary disorder, and although the underlying etiology is not completely known, accumulating evidence supports the role of a neurophysiologic and/or behavioral disease component.5,7,40 Patients with primary premature ejaculation (PPE) have features consistent with a neurophysiologic focus including family history of PE, penile hypersensitivity, excessive ejaculatory reflex, and serotonin receptor sensitivity.40 Stress, anxiety, and emotional problems are consistent with a behavioral theory and have been more closely associated with secondary PE. Several neurotransmitters have been implicated for their role in the complex process of the ejaculatory reflex, with serotonin exhibiting an inhibitory role during ejaculation.41

Diagnosis and treatment outcome measures. A complete assessment of sexual function should be evaluated in order to differentiate ED from PE, which has been reported to co-occur in approximately 30% of patients.40 Complaints involving difficulties maintaining an erection as a result of early ejaculation in the absence of comorbid ED factors could be misdiagnosed as ED if a patient is not properly screened for PE. A short intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT), which is the time from vaginal penetration to ejaculation, can be helpful in establishing the underlying etiology of sexual dysfunction. Recently, the Premature Ejaculation Tool, a valid and reliable measure of premature ejaculation, was developed to capture patient concerns beyond a short latency time.42

Drug therapy treatment options. Although several drugs have been evaluated in clinical trials to improve ejaculatory control and reduce personal distress, none of these agents are currently approved by FDA for the treatment of PE. However, behavior modification strategies and pharmacologic agents such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and topical preparations (eg, lidocaine/prilocaine cream) are all currently recommended by the AUA for the management of PE.5 Topical anesthetics effectively desensitize the penis to tactile stimuli, improve latency time, and are associated with only minor local side effects. The SSRIs and TCAs have traditionally been used as antidepressants and some are associated with intolerable side effects and potentially significant drug interactions, therefore the chronic use of these drugs for the treatment of PE can be unappealing and may result in poor adherence by patients. To address these concerns, several clinical trials have utilized lower doses and on-demand versus continuous daily dosing of these agents, but an advantage associated with this dosing strategy has not been clearly established.5,41

SSRI clinical efficacy. Paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine have been the most studied SSRIs and are commonly recommended agents for the management of PE within their class. Based on results from several randomized controlled trials, paroxetine seems to have the greatest effect on improving IELT and delaying ejaculation from 1.5 min before treatment to 7.7 min after treatment.40,41 Sertraline and fluoxetine have also been shown to increase IELT and improve patient satisfaction, compared to placebo, although fluoxetine's long half-life lends itself to continuous daily dosing rather than on-demand administration.

Precautions and adverse events. The studies that have evaluated the SSRIs for the treatment of PE have generally found these agents to be well tolerated overall, particularly with trials involving patients receiving on-demand treatment. Some of the more commonly reported side effects predominantly occurring in patients on continuous dosing include: nausea, fatigue, headache, confusion, and diarrhea. To minimize potentially serious adverse reactions, patients taking SSRIs should be instructed to avoid taking other serotonergic drugs and advised against abruptly discontinuing therapy. Furthermore, healthcare providers should monitor patients closely for drug interactions, because several SSRIs are highly protein bound and metabolized through the cytochrome P450 system.

Clinical efficacy and safety of TCAs.Clinical trials evaluating the TCAs for the treatment of PE have focused primarily on clomipramine which has been shown to have favorable effects on IELT in several studies.5 In a randomized crossover design involving 36 men with PE who were treated with fluoxetine, sertraline, clomipramine, and placebo, clomipramine had the greatest effect on IELT (from 46 sec at baseline to 5.75 min, P<.01) and patient sexual satisfaction.43 Anticholinergic side effects such as drowsiness, dizziness, dry mouth, and fatigue have been reported in clomipramine-treated patients and may necessitate discontinuation of therapy; on-demand dosing may minimize these effects and improve patient tolerability.

Treatment options currently under investigation. Compared to the array of prospective treatment modalities being studied for patients with erectile dysfunction, future investigational agents for patients with PE to date have not been as promising. The lack of currently approved treatment options by the FDA has further called into question the chronic continuous use of current agents which are viewed as having a questionable risk-to-benefit ratio for the management of PE. Despite these challenges, several agents are being investigated for PE including: SSRIs, serotonin receptor (5-HT1A) antagonists, opioid receptor agonists, PDE 5 inhibitors, and topical preparations.

Dapoxetine, a rapidly absorbed SSRI with a short half-life, has received the most attention of the investigational agents for PE. Despite receiving a non-approvable letter from FDA in 2005, dapoxetine is in phase 3 studies and is currently available in several European countries. Unfortunately the SSRIs BMS-505130 and UK-390957, which had shown some initial promise, no longer appear to be under development.44 The proposed rationale behind the development of the 5-HT1A antagonists for PE is that the coadministration of these agents with the SSRIs may improve the onset of effect in patients who are utilizing on-demand treatment. Combination treatment with pindolol (a non-selective beta blocker with known 5-HT1A antagonist properties) and paroxetine was shown to improve IELT, weekly intercourse episodes, and satisfaction in PE patients who were refractory to paroxetine monotherapy.45 However, combination therapy was also associated with significantly more side effects, which is consistent with the poor tolerability of non-selective beta blockers. Despite several studies that have evaluated the use of sildenafil, vardenafil, or tadalafil, substantial data to support the efficacy of these agents in men with PE, who do not have coexisting ED, is lacking.46

Other currently available agents that have received attention or have limited data for the treatment of PE include tramadol and alpha adrenergic antagonists such as alfuzosin and terazosin. Finally, clinical research focused on topical preparations that have novel delivery formulations, such as a lidocaine/prilocaine metered dose aerosolized spray continue to receive attention because they have demonstrated efficacy and are well tolerated by most patients.44

CONCLUSION

The prompt recognition and management of underlying organic, neurogenic, and psychogenic conditions associated with ED are necessary to improve treatment-related outcomes.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors have now replaced older agents such as alprostadil, phentolamine, and papaverine for the first-line treatment of ED.

The convenience of these oral dosage forms, which have been available for the past decade, has also generated the willingness of more men to seek earlier treatment for their symptoms.

Although premature ejaculation remains one of the most common sexual disorders, the lack of FDA-approved treatments has proven to be a significant challenge for the management of this condition. Despite this obstacle, several agents are currently recommended by the AUA for the treatment of PE such as SSRIs, TCAs, and topical lidocaine/prilocaine. Several investigational drugs for the management of ED and PE are also in various phases of development.

Dr. Douglass is assistant clinical professor, Northeastern University School of Pharmacy, Adult Internal Medicine, Boston Medical Center, Mass. Dr. Lin is a urologist at Massachusetts Bay Urologic Associates, Dorchester Center, Mass.

Disclosure Information: The authors report no financial disclosures as related to products discussed in this article.

REFERENCES

1. American Urological Association. Management of erectile dysfunction: diagnosis and treatment guideline. 2005. Available at: http://www.auanet.org/. Accessed December 4, 2009.

2. Feldman, HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54-61.

3. McKinlay, JB. The worldwide prevalence and epidemiology of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12(suppl 4):S6-S11.

4. Korenman, SG. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction. Endocrine. 2004;23:87-91.

5. Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, et al; AUA Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel. AUA guideline on the pharmacologic management of premature ejaculation. J Urol. 2004;172(1):290-294.

6. McMahon CG, Althof S, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based definition of lifelong premature ejaculation: report of the International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation. BJU Int. 2008;102(3):338-350.

7. Carson C, Gunn K. Premature ejaculation: definition and prevalence. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18 (suppl 1):5-13.

8. Lee M. Erectile dysfunction. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill;2008:1369-1385.

9. Saenz de Tejada I. Molecular mechanisms for the regulation of penile smooth muscle contractility. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12(suppl 4):34-38.

10. Ellsworth P, Kirshenbaum EM. Current concepts in the evaluation and management of erectile dysfunction. Urol Nurs. 2008;28(5):357-369.

11. Rosenberg MT. Diagnosis and management of erectile dysfunction in the primary care setting. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(7):1198-1208.

12. Montague DK, Barada JH, Belker AM, et al. Clinical guidelines panel on erectile dysfunction: summary report on the treatment of organic erectile dysfunction. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1996;156(6):2007-2011.

13. Francis ME, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Eggers PW. The contribution of common medical conditions and drug exposures to erectile dysfunction in adult males. J Urol. 2007;178: 591-596.

14. Montague DK, Jarow JP, Broderick GA, et al; Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel. Chapter 1: The management of erectile dysfunction: an AUA update. J Urol. 2005;174(1):230-239.

15. Viagra [prescribing information]. New York, NY: Pfizer;2007. Available at: http://www.viagra.com/. Accessed December 3, 2009.

16. Levitra [prescribing information]. Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare;2008. Available at: http://www.levitra.com/. Accessed December 3, 2009.

17. Cialis [prescribing information]. Indianapolis, ID: Eli Lilly;2003, rev. 2009. Available at: http://www.cialis.com/. Accessed December 3, 2009.

18. Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel. Chapter 3: Detailed outcomes analyses of treatments for erectile dysfunction. Management of erectile dysfunction: diagnosis and treatment guideline [AUA website]. 2005. Available at: http://www.auanet.org/. Accessed December 4, 2009.

19. Vardi M, Nini A. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors for erectile dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(1):CD002187.

20. DeBusk R, Drory Y, Goldstein I, et al. Management of sexual dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease: recommendations of The Princeton Consensus Panel. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86(2):175-181.

21. Kostis JB, Jackson G, Rosen R, et al. Sexual dysfunction and cardiac risk (the Second Princeton Consensus Conference). Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(suppl 2):1-94.

22. Laties, AM. Vision disorders and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors: a review of the evidence to date. Drug Saf. 2009;32(1):1-18.

23. Caverject [prescribing information]. Kalamazoo, MI: Pharmacia;2003. Available at: http://www.caverject.com/. Accessed December 3, 2009.

24. Linet OI, Neff LL. Intracavernous prostaglandin E1 in erectile dysfunction. Clin Investig. 1994;72(2):139-149.

25. Muse [prescribing information]. Mountainview, CA: Vivus;1998.

26. Urciuoli R, Cantisani TA, Carlini M, Giuglietti M, Botti FM. Prostaglandin E1 for treatment of erectile dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004(2):CD001784.

27. Shokeir AA, Alserafi MA, Mutabagani H. Intracavernosal versus intraurethral alprostadil: a prospective randomized study. BJU Int. 1999;83(7):812-815.

28. Shabsigh R, Padma-Nathan H, Gittleman M, et al. Intracavernous alprostadil alfadex is more efficacious, better tolerated, and preferred over intraurethral alprostadil plus optional actis: a comparative, randomized, crossover, multicenter study. Urology. 2000;55(1):109-113.

29. Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Berlin JA, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(8):2670-2677.

30. Jain P, Rademaker AW, McVary KT. Testosterone supplementation for erectile dysfunction: results of a meta-analysis. J Urol. 2000;164:371-375.

31. Bolona ER, Uraga MV, Haddad RM, et al. Testosterone use in men with sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:20-28.

32. Rhoden EL, Morgentaler A. Risks of testosterone-replacement therapy and recommendations for monitoring. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(5):482-492.

33. Wilson SK, Delk JR, Salem EA, Cleves MA. Long-term survival of inflatable penile prostheses: single surgical group experience with 2,384 first-time implants spanning two decades. J Sex Med. 2007;4(4 Pt 1):1074-1079.

34. Hatzimouratidis K, Hatzichristou DG. Looking to the future for erectile dysfunction therapies. Drugs. 2008;68(2):231-250.

35. Gur S, Sikka SC, Hellstrom WJ. Novel phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the alleviation of erectile dysfunction due to diabetes and ageing-induced oxidative stress. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17(6):855-864.

36. Feifer A, Carrier S. Pharmacotherapy for erectile dysfunction. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:679-690.

37. Gur S, Kadowitz PJ, Hellstrom WJ. A review of current progress in gene and stem cell therapy for erectile dysfunction. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8(10):1521-1538.

38. Melman A, Bar-Chama N, McCullough A, Davies K, Christ G. Plasmid-based gene transfer for treatment of erectile dysfunction and overactive bladder: results of a phase I trial. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9(3):143-146.

39. Melman A, Davies K, McCullough A, Bar-Chama N, Christ G. Long-term safety follow-up of a phase 1 trial for gene transfer therapy of ED with hMaxi-K. J Urol. 2008;179(suppl 4):426.

40. Payne RE, Sadovsky R. Identifying and treating premature ejaculation: importance of the sexual history. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(suppl 3):S47-S53.

41. Giuliano F, Hellstrom WJ. The pharmacological treatment of premature ejaculation. BJU Int. 2008;102:668-675.

42. Symonds T, Perelman MA, Althof S, et al. Development and validation of a premature ejaculation diagnostic tool. Eur Urol. 2007;52:565-573.

43. Kim SC, Seo KK. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine, sertraline and clomipramine in patients with premature ejaculation: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 1998;159(2):425-427.

44. Powell JA, Wyllie MG. 'Up and coming' treatments for premature ejaculation: progress towards an approved therapy. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21(2):107-115.

45. Safarinejad MR. Once-daily high-dose pindolol for paroxetine-refractory premature ejaculation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(1):39-44.

46. McMahon CG, McMahon CN, Leow LJ, Winestock CG. Efficacy of type-5 phosphodiesterase inhibitors in the drug treatment of premature ejaculation: a systematic review. BJU Int. 2006;98(2):259-272.

Employers Face Barriers With Adopting Biosimilars

March 1st 2022Despite the promise of savings billions of dollars in the United States, adoption of biosimilars has been slow. A roundtable discussion among employers highlighted some of the barriers, including formulary design and drug pricing and rebates.