- Safety & Recalls

- Regulatory Updates

- Drug Coverage

- COPD

- Cardiovascular

- Obstetrics-Gynecology & Women's Health

- Ophthalmology

- Clinical Pharmacology

- Pediatrics

- Urology

- Pharmacy

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Allergy, Immunology, and ENT

- Musculoskeletal/Rheumatology

- Respiratory

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Dermatology

- Oncology

New oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: An update for managed care and hospital decision-makers

Atrial fibrillation(AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and a potent risk factor for stroke. Here's a review of new oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention with AF.

Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and a potent risk factor for stroke. AF-related stroke represents a significant economic burden, with an estimated $8 billion in direct annual costs. The new oral anticoagulants have several advantages over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), including a predictable anticoagulation effect that allows for fixed dosing without routine laboratory monitoring, rapid onset and offset of action, and few drug and food interactions. Although acquisition and laboratory monitoring costs of VKAs are low, the time spent by clinicians managing bleeding events and drug interactions, as well as providing patient education, represents a considerable economic burden. Managed care and hospital decision-makers play an integral role in the clinical adoption of new therapeutic modalities, such as new anticoagulant agents, by making multidisciplinary, evidence-based decisions with the goal of improving quality of care while reducing healthcare costs. (Formulary. 2012;47:299–305.)

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, and it affects approximately 1% to 2% of the general population.1 The risk of developing AF increases substantially with age, and its prevalence is projected to increase 2.5-fold by 2050, thus increasingly affecting the elderly, Medicare-aged population.2 A diagnosis of AF confers a 5-fold increase in the risk for stroke, with 1 in 5 strokes attributable to AF.1 Importantly, strokes that occur as a result of AF are more debilitating than strokes attributable to other causes, and patients who survive an AF-related stroke are more likely to experience a recurrence.1,3 Consequently, AF-related stroke represents a significant economic burden on the healthcare system, with an estimated $8 billion in direct annual costs.4

Managed care and hospital decision-makers play an integral role in the institutional adoption of recently approved therapeutic modalities by making multidisciplinary, evidence-based decisions with the goal of improving the quality of care while reducing healthcare costs. A robust understanding of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants, as well as their implications for the healthcare system, is therefore essential.

TRADITIONAL AGENTS

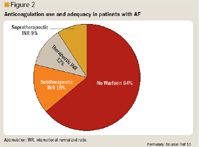

Despite evidence-based recommendations for stroke prophylaxis with VKAs, they remain underprescribed in eligible patients with AF.11 A study by Choudhry et al. demonstrated that physicians with a patient that experienced a major bleeding event were less likely to prescribe a VKA in eligible patients with AF.12 In another study, Caro analyzed the potential economic burden of suboptimal oral anticoagulation in patients with AF.4 The author documented that approximately 55% of patients with AF do not receive adequate stroke prophylaxis and, as a result of increased incidence of stroke, estimated the annual total direct costs to Medicare for these patients at $4.8 billion.4

NEW ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

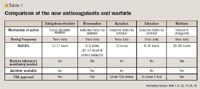

The new oral anticoagulants have potential advantages over VKAs, including a predictable anticoagulation effect that allows for fixed dosing, rapid onset and offset of action, and few clinically relevant drug and food interactions. In addition, the new oral anticoagulants have a much wider therapeutic index compared with VKAs, obviating the need for routine laboratory monitoring. Monitoring has been explored using the ecarin clotting time assay (dabigatran) and the anti-factor Xa assay (rivaroxaban and apixaban), which may be useful in specific emergency situations.15,16,17 Although no direct antidotes for the new oral anticoagulants have been identified thus far, prothrombin complex concentrates are being explored for use in reversal.18

Dabigatran etexilate

Dabigatran etexilate is FDA approved for reducing the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular AF at a dose of 150 mg orally twice daily (75 mg orally twice daily if creatinine clearance [CrCl] is 15–30 mL/min).7 In addition, the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association Task Force released a focused update in 2011 to include dabigatran etexilate.19 In these guidelines, dabigatran etexilate is recommended as an alternative to warfarin in patients with paroxysmal or permanent AF; risk factors for stroke or systemic embolism; and who do not have prosthetic heart valves, hemodynamically significant valve disease, severe renal failure, or advanced liver disease.19 However, the guidelines state that patients already taking warfarin with excellent INR control may derive little benefit from switching to dabigatran.19 This recommendation was based on findings from the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) study.19

The RE-LY study randomized patients to receive 110 mg or 150 mg of oral dabigatran etexilate twice daily or unblinded warfarin titrated to an INR of 2.0 to 3.0 to evaluate the primary end point: the composite of stroke and systemic embolism.20 Based on the CHADS2 classification scheme (C, congestive heart failure; H, hypertension; A, age; D, diabetes; S2, stroke/transient ischemic attack), patients enrolled in RE-LY had a mean score of 2.1. CHADS2 uses patient characteristics to give an estimate for an individual's risk of stroke (in a range of 0–6), with higher scores corresponding to a higher risk of stroke.21

In patients who received 110 mg or 150 mg of dabigatran etexilate, the rate of primary end point was 1.53% and 1.11%, respectively, compared with 1.69% in patients who received warfarin (both P<.001 for noninferiority). Although both doses of dabigatran etexilate demonstrated noninferior efficacy to warfarin, only the 150-mg dose resulted in superiority (P<.001).20 The annual rate of major bleeding events was significantly lower, at 2.71%, in the group receiving 110 mg of dabigatran etexilate compared with the warfarin-treated arm (3.36%; P=.003). Patients treated with 150 mg of dabigatran etexilate experienced similar rates of major bleeding events as those in the warfarin arm (3.11%; P=.31). Higher rates of dyspepsia were observed in the 110-mg (11.8%) and 150-mg (11.3%) dabigatran etexilate groups compared with the warfarin group (5.8%; P<.001 for both comparisons); and a significantly higher rate of myocardial infarction was observed in the 150-mg dabigatran etexilate group (0.72% per year) compared with the warfarin group (0.53% per year; P=.048). Significantly lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage were observed in both the 110-mg (0.23%) and 150-mg (0.3%) dabigatran etexilate groups compared with the warfarin group (0.74%; P<.001 for both comparisons).20

Although both doses of dabigatran etexilate, 110 mg and 150 mg twice daily, demonstrated noninferior efficacy to warfarin in the RE-LY study, only the higher dose has been approved by the FDA. This decision was based on an inability to identify any subgroup of patients in which use of the lower dose would not represent a substantial disadvantage compared with use of the higher dose.22

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban is a selective oral factor Xa inhibitor that binds directly to factor Xa, the product of both intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways, to effectively block the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin (Figure 1). Rivaroxaban has few clinically relevant drug interactions; however, it is a substrate for both P-gp and CYP3A4, so combined P-gp and strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers should be avoided.8

Rivaroxaban is now FDA approved to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular AF at a dose of 20 mg once daily with the evening meal (15 mg once daily with the evening meal if CrCl is 15–50 mL/min).8

In the Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF) study, 14,264 patients with AF were randomized to receive either 20 mg of oral rivaroxaban once daily or blinded warfarin titrated to an INR of 2.0 to 3.0. The study was double-blinded, and the primary end point consisted of the composite of stroke and systemic embolic events.23 Compared with other recent studies evaluating the new oral anticoagulants for AF, patients enrolled in ROCKET AF had a relatively high number of comorbidities and a high risk of stroke at baseline, with a mean CHADS2 score of 3.5. In addition, the mean proportion of time in which the intensity of warfarin anticoagulation was in the therapeutic range was lower for patients enrolled in the ROCKET AF study (55%) than for those enrolled in studies of other new anticoagulants in patients with AF (range, 64%–68%). This may reflect regional differences and differential skill in managing warfarin at trial centers involved in the ROCKET AF study.23

Patients taking rivaroxaban or warfarin had similar rates of the primary end point and of major bleeding events.23 The rate of the primary end point in the rivaroxaban arm was 2.1% per year, compared with 2.4% per year in the warfarin arm (P=.12). The annual rates of major bleeding events were 3.6% and 3.4% in the rivaroxaban and warfarin arms, respectively (P=.58). However, rates of intracranial hemorrhage were lower in participants taking rivaroxaban (0.5% vs 0.7%; P=.02).23 At the conclusion of the study, patients who discontinued rivaroxaban and were restarted with warfarin or other VKAs were observed to be at an increased risk for stroke. It should be noted that no overlapping anticoagulant therapy was used, so patients may not have had adequate stroke prophylaxis until warfarin was therapeutic. The observation of increased stroke led to a black-box warning in the prescribing information recommending that if anticoagulation with rivaroxaban must be discontinued for any reason other than pathologic bleeding, administration of another anticoagulant should be considered.8

Apixaban

Apixaban is another factor Xa inhibitor (Figure 1). A phase 3 study to evaluate its utility for stroke prophylaxis in patients with AF was completed recently. Like the other new anticoagulants, apixaban has a low propensity for clinically relevant drug interactions. Nonetheless, because it is a substrate for P-gp and CYP3A4, concomitant use with strong inhibitors or inducers requires extra caution.24

Apixaban was first compared with aspirin for prophylaxis of AF-related stroke in the Apixaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid to Prevent Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Who Have Failed or Are Unsuitable for Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment (AVERROES) study.25 AVERROES was ended early based on a recommendation by the data and safety monitoring board, which determined that there was an exceptionally clear efficacy benefit to the use of apixaban compared with aspirin in an interim analysis.

Apixaban was compared with warfarin for stroke prophylaxis in patients with AF in the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) study.13 Patients were randomized to receive either 5 mg of oral apixaban twice daily or warfarin (titrated to an INR of 2.0–3.0) to evaluate the primary end point of stroke and systemic embolism events. The apixaban arm demonstrated a significant reduction in the primary end point, with a rate of 1.27% per year compared with 1.60% per year in the warfarin arm (hazard ratio [HR], 0.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–0.95; P<.001 for noninferiority, P=.01 for superiority). Patients enrolled in ARISTOTLE had a mean CHADS2 score of 2.1. The incidence of major bleeding events was also significantly lower in the apixaban arm, with an annual rate of 2.13% compared with 3.09% in the warfarin arm (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.60–0.80; P<.001). In addition, significantly lower rates of mortality (3.52% vs 3.94%, P=.047) and intracranial hemorrhage (0.33% vs 0.80%, P<.001) were observed in patients taking apixaban.

Edoxaban

Edoxaban is a highly specific small-molecule factor Xa inhibitor that can be administered orally (Figure 1). Although it is a substrate of P-gp, CYP3A4 is not extensively involved in the metabolism of edoxaban; this may translate into even fewer potential drug–drug interactions than other factor Xa inhibitors.26

Edoxaban is being evaluated in the Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Study 48 (ENGAGE-AF TIMI 48), which includes patients with AF and an intermediate to high risk of thromboembolic events (CHADS2 score ≥2).14 Patients were randomized to receive 30 mg or 60 mg of oral edoxaban once daily or warfarin (adjusted to an INR of 2.0–3.0). The ENGAGE-AF TIMI 48 study is ongoing, and results are anticipated in late 2012.

POTENTIAL ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF THE NEW ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

In a prospective cohort study of elderly patients with AF by Metlay et al., the rate of hospitalization for warfarin-related bleeding events was 4.6 events per 100 person-years of exposure; the risk of experiencing a serious bleeding event was significantly reduced by receiving medication instructions from a physician or a nurse plus a pharmacist.30 Hospitalizations due to warfarin-related bleeding events are costly. A study by Kim et al. documented a mean cost of $10,819 (standard deviation, $11,536) for such hospitalizations; in addition, it was demonstrated that instruction regarding warfarin management from a healthcare professional may reduce such hospitalizations and associated costs.28

Although relatively infrequent, intracranial hemorrhage represents not only the most-feared bleeding complication of warfarin but also the most costly adverse event for patients who survive it. Gastrointestinal bleeding, either major or minor, also represents a significant concern for clinicians. In a retrospective analysis of 47,437 patients with AF taking warfarin for stroke prophylaxis, 194 (0.4%) experienced an intracranial hemorrhage, and 919 (1.9%) had a major gastrointestinal bleeding event.27 A generalized linear model revealed that annual all-cause costs were 64.4% and 49.0% higher for patients who experienced intracranial hemorrhage or a major gastrointestinal bleeding event, respectively, compared with patients who experienced no bleeding events (P<.001 for both comparisons).27

Although much harder to quantify than the costs of complications due to warfarin, time spent by clinicians and patients, as well as transportation costs incurred by patients, represent another significant contribution to the cost of warfarin management. A study by Jonas et al. demonstrated that patients spent an average of 39 hours on anticoagulation clinic visits and an average of 52.7 hours on other related activities, such as communicating with providers and pharmacy trips.31 Using the human capital method to estimate the value of time, the annual value of patient time spent for anticoagulation visits was $707 (median, $591) and, when other anticoagulation-related activities were included, this value further increased to $1,799 (median, $1,132).31

The cost effectiveness of dabigatran versus warfarin has been assessed in a number of countries on the basis of data from the RE-LY study.32-39 In general, these studies suggest that dabigatran is more cost effective than warfarin for older patients, patients at a high risk of stroke or intracranial hemorrhage, and in situations in which INR control of warfarin is poor. According to a study conducted in the United Kingdom, however, on the basis of the current price of dabigatran, warfarin remains suitable for the majority of patients with AF.40

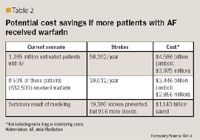

Although individual cost-effectiveness analyses are awaited for rivaroxaban and apixaban, a recent study in the United States used existing phase 3 study data to calculate the medical cost savings associated with these agents and dabigatran.41 Excluding drug costs, use of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban was estimated to result in annual savings of $179, $89, and $485 per patient-year, respectively, compared with warfarin.41

CONCLUSION

Despite the efficacy of warfarin in reducing stroke in patients with AF, AF-related stroke remains a substantial source of morbidity, mortality, and financial burden. A large number of preventable thrombotic events may result in a higher-than-necessary cost of care. The practical management aspects of warfarin, including necessary routine laboratory monitoring, patient education, and management of bleeding events, contribute substantially to its cost of care. The new oral anticoagulants, which are either approved for stroke prophylaxis in patients with AF or have completed phase 3 studies, may not only represent therapeutic alternatives to warfarin, they also may be as cost effective or may convey cost savings, if they result in fewer bleeding or thrombotic complications. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the cost benefit of the new oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin.

Dr Amin is professor of medicine, University of California, Irvine's School of Medicine, Irvine, Calif.

Disclosure Information: The author reports research funding and/or speakers bureau participation for sanofi-aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Johnson & Johnson, and NovoSys.

The author acknowledges Matthew Romo, PharmD, who provided editorial support with funding from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

REFERENCES

1. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010;31(19):2369–2429.

2. Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2370–2375.

3. Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Reith J, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Acute stroke with atrial fibrillation. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke. 1996;27(10):1765–1769.

4. Caro JJ. An economic model of stroke in atrial fibrillation: the cost of suboptimal oral anticoagulation. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(14 suppl):S451–S458.

5. You JJ, Singer DE, Howard PA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e531S–e575S.

6. Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123(10):e269–e367.

7. Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate mesylate) [prescribing information]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc;2011.

8. Xarelto (rivaroxaban) [prescribing information]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc;2011.

9. Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):160S–198S.

10. Bungard TJ, Ackman ML, Ho G, Tsuyuki RT. Adequacy of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation coming to a hospital. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(9):1060–1065.

11. Darkow T, Vanderplas AM, Lew KH, Kim J, Hauch O. Treatment patterns and real-world effectiveness of warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation within a managed care system. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(10):1583–1594.

12. Choudhry NK, Anderson GM, Laupacis A, Ross-Degnan D, Normand S-LT, Soumerai SB. Impact of adverse events on prescribing warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: matched pair analysis. BMJ. 2006;332(7534):141–145.

13. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al; ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981–992.

14. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Antman EM, et al. Evaluation of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: design and rationale for the Effective aNticoaGulation with factor x. A next GEneration in Atrial Fibrillation--Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction study 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48). Am Heart J. 2010;160(4):635–641.

15. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate-a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(6):1116–1127.

16. Samama MM, Contant G, Spiro TE, et al; Rivaroxaban Anti-Factor Xa Chromogenic Assay Field Trial Laboratories. Evaluation of the anti-factor Xa chromogenic assay for the measurement of rivaroxaban plasma concentrations using calibrators and controls. Thromb Haemost. 2011;107(2):379–387.

17. Becker RC, Yang H, Barrett Y, et al. Chromogenic laboratory assays to measure the factor Xa-inhibiting properties of apixaban-an oral, direct and selective factor Xa inhibitor. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;32(2):183–187.

18. Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, Meijers JC, Buller HR, Levi M. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124(14):1573–1579.

19. Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (update on dabigatran): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(11):1330–1337.

20. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139–1151.

21. Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285(22):2864–2870.

22. Beasley BN, Unger EF, Temple R. Anticoagulant options-why the FDA approved a higher but not a lower dose of dabigatran. N Engl J Med. 2011;12;364(19):1788–1790.

23. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al; ROCKET AF Investigators. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883–891.

24. Eliquis (apixaban) [summary of product characteristics]. Middlesex, UK: Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer EEIG;2011.

25. Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, et al; AVERROES Steering Committee and Investigators. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):806–817.

26. Chung N, Jeon H-K, Lien L-M, et al. Safety of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, in Asian patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(3):535–544.

27. Ghate SR, Biskupiak J, Ye X, Kwong WJ, Brixner DI. All-cause and bleeding-related health care costs in warfarin-treated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(9):672–684.

28. Kim MM, Metlay J, Cohen A, et al. Hospitalization costs associated with warfarin-related bleeding events among older community-dwelling adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(7):731–736.

29. Eckman MH, Rosand J, Greenberg SM, Gage BF. Cost-effectiveness of using pharmacogenetic information in warfarin dosing for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(2):73–83.

30. Metlay JP, Hennessy S, Localio AR, et al. Patient reported receipt of medication instructions for warfarin is associated with reduced risk of serious bleeding events. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1589–1594.

31. Jonas DE, Bryant SB, Laundon WR, Pignone M. Patient time requirements for anticoagulation therapy with warfarin. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(2):206–216.

32. Freeman JV, Zhu RP, Owens DK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(1):1–11.

33. Shah SV, Gage BF. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran for stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2011;123(22):2562–2570.

34. Sorensen SV, Kansal AR, Connolly S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation: a Canadian payer perspective. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(5):908–919.

35. Adcock AK, Lee-Iannotti JK, Aguilar MI, et al. Is dabigatran cost effective compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation? a critically appraised topic. Neurologist. 2012;18(2):102–107.

36. Kamel H, Johnston SC, Easton JD, Kim AS. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2012;43(3):881–883.

37. Kansal AR, Sorensen SV, Gani R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in UK patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2012;98(7):573–578.

38. Langkilde LK, Bergholdt AM, Overgaard M. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Applying RE-LY to clinical practice in Denmark. J Med Econ. 2012: Epub Mar 22.

39. Pink J, Lane S, Pirmohamed M, Hughes DA. Dabigatran etexilate versus warfarin in management of non-valvular atrial fibrillation in UK context: quantitative benefit-harm and economic analyses. BMJ. 2011;343:d6333.

40. Ali A, Bailey C, Abdelhafiz AH. Stroke prophylaxis with warfarin or dabigatran for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation-cost analysis. Age Ageing. 2012: Epub Feb 28.

41. Deitelzweig S, Amin A, Jing Y, et al. Medical cost reductions associated with the usage of novel oral anticoagulants vs. warfarin among atrial fibrillation patients, based on the RE-LY, ROCKET-AF and ARISTOTLE trials. J Med Econ. 2012: Epub Mar 27.

42. Coumadin (warfarin sodium) [prescribing information]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharma Company;2011.

Coalition promotes important acetaminophen dosing reminders

November 18th 2014It may come as a surprise that each year Americans catch approximately 1 billion colds, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that as many as 20% get the flu. This cold and flu season, 7 in 10 patients will reach for an over-the-counter (OTC) medicine to treat their coughs, stuffy noses, and sniffles. It’s an important time of the year to remind patients to double check their medicine labels so they don’t double up on medicines containing acetaminophen.

Support consumer access to specialty medications through value-based insurance design

June 30th 2014The driving force behind consumer cost-sharing provisions for specialty medications is the acquisition cost and not clinical value. This appears to be true for almost all public and private health plans, says a new report from researchers at the University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design (V-BID Center) and the National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC).

Management of antipsychotic medication polypharmacy

June 13th 2013Within our healthcare-driven society, the increase in the identification and diagnosis of mental illnesses has led to a proportional increase in the prescribing of psychotropic medications. The prevalence of mental illnesses and subsequent treatment approaches may employ monotherapy as first-line treatment, but in many cases the use of combination of therapy can occur, leading to polypharmacy.1 Polypharmacy can be defined in several ways but it generally recognized as the use of multiple medications by one patient and the most common definition is the concurrent use of five more medications. The presence of polyharmacy has the potential to contribute to non-compliance, drug-drug interactions, medication errors, adverse events, or poor quality of life.

Medical innovation improves outcomes

June 12th 2013I have been diagnosed with stage 4 cancer of the pancreas, a disease that’s long been considered not just incurable, but almost impossible to treat-a recalcitrant disease that some practitioners feel has given oncology a bad name. I was told my life would be measured in weeks.